Todo Sobre Mi Madre

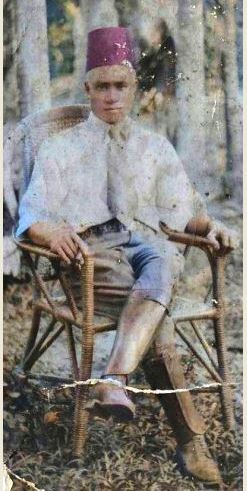

My mother was born in Malita, Davao del Sur in 1918 to Sheikh Ismail Yahya, a Mranao Arab and Bai Rosa, a Buayanen / Maguindanaon princess and coconut plantation heiress.

And as my mother used to say, she was “born with a silver spoon in her mouth.”

By the age of 12, my mother had her own Arabian horse and her own car. When the Americans came to Lanao, they urged the Mranaos to send their children to school. There was compulsory education. But the datus refused to let their children attend school for fear that they would be converted to Christianity. To appease the Americans, the Mranao datus sent the children of their slaves instead.

Sheikh Ismail, who was a school superintendent, sent my mother to a boarding school run by the Thomasites in Lanao. When the datus of Bayang, Sheikh Ismail’s hometown, heard about it, they surrounded the school and demanded that my mother be released to them immediately. The datus did not like the idea that my mother would be classmate to children of slaves.

My mother’s grandmother wanted to send her granddaughter to the US like the two Tausug princesses who were sent by the American government to the US for studies. Her grandmother’s advisers had even chosen the school for her – Bryn Mawr College. But, the sheikh would not hear of it. As a compromise, my mother was sent to a school in Cebu – far from the Mranao datus but not too far from the Sheikh.

The Heiress and the Lawyer

Three of the first Moro lawyers – Macapanton Abbas, Domocao Alonto and Salipada Pendatun vied for my mother’s hand. (Alonto and Pendatun later became senators.) Her classmates in Cebu, who later became business tycoons, also courted her.

During the wake of my uncle in 1977, one business tycoon from Cebu told me that when they were younger, he was in love with my mother but would not dare court her because he was intimidated by her riches.

My mother was quite fond of telling us how the three Moro law students tried to outdo one another. One day, she was called to the office of the dorm’s house mistress, a stern American lady. She told my nervous mother that 3 letters arrived that day from 3 gentlemen. She told her in no uncertain terms that the house frowns upon gentlemen callers and their letters.

She found out much later that on that day, one of those guys told the other two that my mother just wrote to him and accepted his marriage proposal. Thus, he was on his way to the post office to send his letter expressing joy and sending his love. The two other guys, immediately ran to their rooms — they all lived in the same dorm — and wrote their own letters. And so, the three letters arrived in Cebu, from Manila, at the same time.

My mother chose the very first Moro lawyer to graduate and pass the Bar – my father. But it was not love at first sight for my mother. She actually preferred another suitor, a Spanish Filipino. But she lived in Davao while he lived in Cebu. Her mother and his mother saw to it that their letters would not reach each other. When both my mother and her suitor did not receive replies to their letters, they thought the other simply fell out of love. It was only when they met after World War II that they realized their mothers had intercepted their love letters. Just like in old Filipino movies!

My mother’s modern ways created a stir in conservative Marawi. My father’s family was scandalized when my parents walked hand in hand in public. They were shocked when my mother wore slacks and even played tennis at the Lanao country club. Once, the late Ambassador Mauyag Tamano told us that when my mother arrived in Marawi in 1936, he and other male kids would hide themselves in trees or houses and follow her when she would come walking down the streets of Marawi. They all had a crush on her.

In Malita, Sitti Rahma was the darling of everyone – her grandparents, her father and the people. She only had to contend with her mother, who was partial to her brother Abdul Kader (Qadir). But in Marawi, my mother met adversaries everywhere. My father was the darling of his family and his female relatives – mother, aunts and great aunts — all looked with disfavor on my mother whom they regarded as a foreigner. The Mranaos are very endogamous and prefer to marry within their pangampong (traditional state or principality).

In Mranao society, like in most Arab societies, the extended household is controlled by women – mothers, aunts and elder sisters. After a year of being dominated by her female in-laws in Marawi, my mother told her servants to pack up and drove back to her father in Davao. My grandfather offered to give back my father’s dowry but he refused. My father asked for a second chance. My mother calmed down and agreed to go back to Marawi, but this time she insisted that her mother come along.

HEROIC STRUGGLE IN WWII

World War II brought great suffering to most of the world. My mother was not exempted from that. She had a happy marriage with four little children. They lived in Marawi where my father, as a young lawyer, started taking the role of leader of his clan. My mother’s father just died so her mother, who lived in Davao, decided to stay with them.

When the Japanese came, my father wanted to join the guerrilla movement but she forbade him to join. She told him that she could not possibly take care of so many children alone. The Japanese who came to Lanao did not brutalize the people as they did in Luzon. According to my mother, the Japanese officers were from Japan’s nobility and acted in a courteous and civilized manner. The Japanese invited the young Mranao leaders to be the province’s officials – governor, mayor, etc. My father was invited to be one of the new government’s leaders. He refused. The Japanese then called a manhunt for him.

For months, my parents, my grandmother, my four eldest sisters (the youngest was a mere infant) were on the run, together with their servants. They ran from one village to another, staying with relatives or in the community’s torogan (royal house). But the running was too much for the youngest daughter, Salma. She died. It was then that my father decided to surrender to the Japanese.

According to my mother, upon hearing that my father surrendered, most, if not all his cousins, uncles and relatives (that would be quite a lot since he belonged to so many royal houses of Lanao) surrounded the house of the Japanese commander and refused to leave unless my father would leave with them. The Japanese commander released my father on the condition that he would be appointed as Justice of the Peace.

But a judge’s salary was a mere pittance since the Japanese money was practically worthless. To survive, my mother had to cook Mranao “pancakes” and sold them in the marketplace. She and her mother cooked the pancakes every night and the servants and my father’s younger half-brothers sold them in the market every morning.

In the middle of World War II, she gave birth to her eldest son – Macapanton, Jr., to the extreme delight of my father who had been wishing for a male heir for so long. But Junior later developed meningitis and the only doctor in Lanao refused to cure him if he was not paid in real Philippine pesos or US dollars or gold. He was the only one who had penicillin in the province (the whole Lanao – del Sur and del Norte). My mother did not have enough money from her pancakes. She had to pay the Christian doctor her necklace made of Spanish doubloons (gold coins). Thus, Macapanton, Jr. survived meningitis and World War II.

As the war drew on, my mother became president of the Melchora Aquino society. Melchora Aquino or popularly known as Tandang Sora was a heroine of the Philippine Revolution. Tandang Sora was a rich old lady who fed and housed the sick and wounded revolutionaries. As the society’s president, my mother taught the Mranao ladies how to cook, to sew bed sheets and curtains, to properly fix the linens on the bed and set the table. She taught them the skills so when the guerrillas or relatives on the run would come to them, they would know how to properly care for them.

They also had a radio, which became very important to the resistance as they were able to obtain information.

My father, on the other hand, was able to free several guerrillas by dismissing their cases. Once, three top guerrillas were caught by the Japanese. The Japanese commander sent him a note to detain the prisoners at all costs. Upon receiving the note, he immediately called the guerrillas, briefly interviewed them and let them go. When confronted by the angry Japanese commander, he simply reasoned out that according to the orders of Philippine President Jose Laurel, all accused should be freed if there were no concrete evidence against them.

When the Americans came, practically every Mranao claimed to be a guerrilla and got their “back pay”, a considerable amount. My father was sent a telegram by the US Army to get his “back-pay” with the rank of Major. According to the Provost Marshall, his actions as a judge and the information the Resistance got from him through the radio were very important and helpful. He was thus considered to be a covert member of the Resistance. But my father, being who he was, refused to get his Army commission and back pay.

In fact, one of his former slaves came to him bringing his (the former slave’s) back pay. His former servant asked him to get as much money he wanted. Of course, he refused. My father freed all his slaves after he married my mother.

On the other hand, my mother was acknowledged by the USAFFE for her activities as head of the Melchora Aquino Society. The Provost Marshall, in a public ceremony, gave her bales of cotton and other fabrics as a reward for her covert war efforts. Like my father, she refused the donation. She reasoned that the Melchora Aquino Society was created during the Japanese-Philippine government and was not accredited by the American-Philippine government. She said that she did what she did, not because she wanted to fight the Japanese but merely to help her fellow Mranao ladies.

The woman who was born “with a silver spoon in her mouth” suffered so much during the war. She used to say that before the war, a pair of shoes that she used to order from Manila would cost her way more than the equivalent of a teacher’s monthly salary. During the war, she became the family’s bread winner. Her ancestral home in Davao was burnt to the ground by the Japanese. Her mother’s, her brother’s and her own coconut plantations were also destroyed. She therefore extracted a promise from my father that after the war, he would go into business and concentrate on making money. My father never made good his promise. He remained with the government as provincial fiscal, district judge and CFI judge. In 1964, when he was supposed to be appointed to the Court of Appeals by Pres. Macapagal, his law school classmate and former barkada, he died.

My mother was able to get a logging concession from a bank in Davao City. But when my father learned of it, he demanded that she return it as he didn’t want to have debts. My mother finally sold it to her compadres (brothers who were godfathers to me and my youngest sister) for a song. The brothers became multi-millionaires.

The Tausug princesses and my mother

In the 1950s, my father was appointed Provincial Fiscal, District Judge , and CFI Judge of Sulu. My grandmother, Bai Rosa was a first cousin of Sultan Zein ul-Abidin II (pronounced locally as Jainal Aberrin II). Naturally, my mother insisted that her mother join them in Sulu. And so my mother became very close to her cousin Dayang dayang Inda Taas, the Sultan’s daughter and to her idol Dayang dayang Putli Tarhata, the Sultana or Pangyan of Sulu and sister-in-law of the Sultan. The three became very close friends.

When my mother was in Grade VI in Cebu, her declamation piece was about the celebrated Princess Tarhata Kiram of Sulu. She was so excited when she finally met her in Jolo and became very good friends. When Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia came to Manila in the 1950s, the Tausug princesses and my mother were invited for dinner at Malacanang. According to my mother, they had a good laugh a day later when the Manila papers described them as Indonesian princesses. Apparently, Manila journalists did not believe that there were princesses in the Philippines.

My mother had so many stories about her time in Sulu with her cousins. In those times, royalty hardly mixed with commoners, including politicians. One time, there was a party in honor of some foreign ambassadors. My mother was, as usual, with her two best friends. At that time, a young Mranao princess was with them. When the ambassadors were approaching them, the eager Mranao lady immediately stood up. Dayang dayang Tarhata pulled her down and reminded her that they were princesses; and, ambassadors come to princesses and not the other way around.

Frustrated lawyer

It was quite unfortunate that my mother did not finish law school. According to her, when her second son fell down the stairs and had his head bloodied, my father asked her to choose whether to be a mother or to be a lawyer. She already had lost one child during World War II when the Japanese were hunting down my father and they had to run all over Lanao. She chose to be a mother. She bore fourteen children. I am the 13th child.

When her high school classmate and close friend Mary Concepcion-Bautista was appointed by President Cory Aquino as PCGG Commissioner, I kidded her that had she finished law, she probably would be strong and healthy as Manang Mary instead of being sickly. But she actually outlived her good friend MaryCon, who used to call her “my idol”.

In her hometown in Malita, she was a legend. The last time I was there in 1990, people still talked in awe of her. She was a great campaigner. She was an indefatigable campaigner for her brother, the Mayor of Malita. She was instrumental in her son-in-law’s victory as Vice Governor of Lanao. “I opened the political doors for him,” she used to say. In the early 1960s, the Liberal Party wanted her to run as Congresswoman in Davao. But she refused because my father did not approve of it.

Political Campaigner

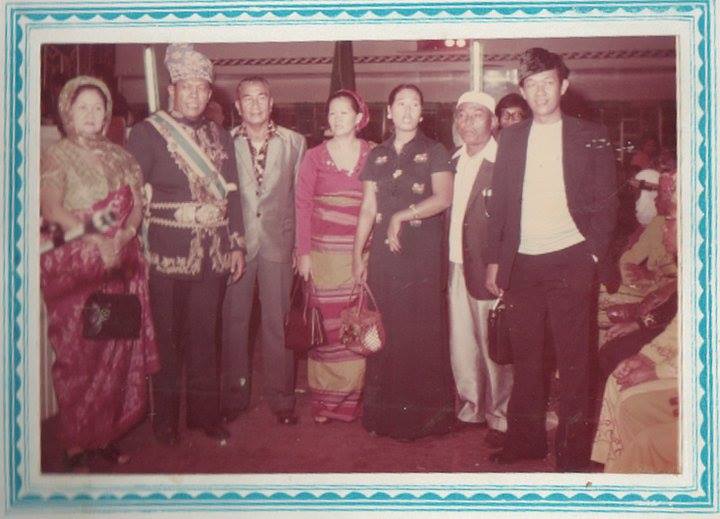

In 1969, she became a very close friend of Nana Sepa (Dona Josefa Edralin Marcos), President Marcos’s mother. She and Nana Sepa created Operation Pepay, which organized teams of ladies all over the country to campaign for the re-election of President Marcos and the election of her son-in-law Mamintal Tamano as senator. She brought the President’s mother all over Mindanao to campaign. Because of security reasons, Marcos himself did not campaign in Sulu. But my mother brought the President’s mother there where she was met at the airport by my mother’s cousin, the Sultan of Sulu Jamal ul Abidin (Jamalul Aberrin) of the Patikul branch of Sulu royalty. In Lanao, huge crowds met them everywhere. She was even carried on a gilded chair. Photos of the Nana Sepa’s Mindanao campaigns can be seen at her old house (now turned into a museum) in Ilocos Norte.

I remember accompanying my mother in one of those campaigns. I was 10 years old then. We were on an airplane from Davao to Manila. I was surprised when my mother ordered a cot to be opened so she could lie there. And when I walked towards the cockpit, I was amazed to see Nana Sepa and three other ladies playing mahjong with a mahjong table and all!

It is so ironic that after campaigning so hard in 1969 for Marcos, my eldest brother would turn out to be a Marcos opponent. Marcos had him detained when he suspended the writ of habeas corpus and when he declared Martial Law. My brother was detained for a day or so the first time and about a month the second time. In 1977, Macapanton, Jr. escaped from the country with some forged travel documents. He went into self-exile in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. At that time, I was studying at the University of Petroleum and Minerals in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. In 1978, my mother suffered a massive stroke. But she survived. In 1979, she joined my brother in Jeddah.

My mother loved city life. She refused to stay either in Lanao or in her hometown in Davao. Jeddah did not have the usual fares one finds in a city – cinemas, casinos, etc. I asked her what made her come to Jeddah. She said she got an “invitation” from the military. During Martial Law, an “invitation” from the military could mean many things – from simple questioning to third-degree interrogation to even extra-judicial killing (also called “salvaging”). My mother stayed in Jeddah until 1983. She was not an OFW. She was there as guest of the Saudi royal family.

One day in Jeddah, some Mranaos came over to consult with my brother. My mother greeted them and left. One of them asked me if she was my mother. I said yes. He said he could still remember the time when my mother delivered on radio a fiery speech against the political enemies of her son-law, Mamintal Tamano, who was running for governor. “She was so brave. She lambasted practically all the political leaders then,” he told me. It was obvious that the guy was still in awe of my mother. I had heard of that speech. It was the first time that somebody attacked the political leaders publicly and in such a scathing manner.

A Polyglot

Her children never encouraged her to excel in anything. Every time she mentioned that she wanted to write a book about Mindanao, her elder children were the first to discourage her. Yet she was a great storyteller and certainly was more knowledgeable about the Moros and Mindanao than her children. She could speak fluently Mranao, Tausug, Maguindanao, Manobo, Tagakaulo, Chavacano, Ilocano, Cebuano, Tagalog and English.

But then she reared her children to become prima donnas. And prima donnas do not want to have a powerful mother. She already had a very strong personality. Perhaps her elder children did not want her to have political power as well.

Because my mother never became a government official or a politician, posterity would not hear or read of her. Officially, she is unknown. Even the fact that she was the first Miss Malita (ca. 1930) is not recorded. There are no records that show that as President of the Melchora Aquino society in Lanao during WWII, she taught Mranao ladies proper household chores like setting up a table, handling linens, sewing curtains and pillows, etc. She was instrumental in the charter of the ship MV Gambela that enabled thousands of Moros to go on pilgrimage to Mecca in 1968. And she was an indefatigable campaigner.

Some people forget easily. But many don’t. When my brother ran for Con-Con delegate in 1971, he was very confident of winning. With his senator brother-in-law at his side and being with the ruling Nationalista Party, my brother thought he did not need my mother to campaign at all. I remember vividly the time when my brother returned to Manila for a respite from the campaign. He was over-confident. Our mother asked him if he wanted her to go to Lanao to campaign. “No need,” my brother said. “I’d say I have at least 70% of the votes,” he boasted. He was against the old politicians of the province, my parents’ contemporaries. He lost.

Later, an aunt told us that there was no way for him to win, especially in Bayang, my mother’s (actually, her father’s) hometown. Our aunt told us, everywhere they went, the people kept on telling her and her sister and brothers that if Sitti Rahma wanted her son to win, then she would have been there campaigning for him. Our aunt said that any excuse they gave was lame because everyone knew that my mother campaigned vigorously for her son-in-law in 1969 and earlier in his runs for senator, governor and vice-governor.

On hindsight, I think that had my mother campaigned for my brother then, he would have won. She could have easily raised campaign funds, just as she did in my brother-in-law’s political campaigns. She merely wanted to be asked. My brother-in-law asked for her help when he ran for Vice Governor and Governor. And Dona Josefa asked for her help to campaign for Marcos in 1969. My mother knew that it needed a huge war chest to wage an election campaign. On the other hand, I don’t think my brother even had a war chest. He probably thought it was just like campus politics, of which he had a lot of experience. He merely depended on party funds. He was just a few years out of law school.

Movie buff and Party hostess

My mother was such a movie buff. I must have seen hundreds of movies with her. She and her brother used to spend hours watching silent films in their childhood in the 1920s. Their favorite was the cowboy star Tom Mix. She had seen practically all movies shown in the Philippines from her childhood up to the time she became bed-ridden. When she was in her teens, she used to bring the seamstress with her to the movies so the seamstress could sew the same clothes for her as the lead actresses in the movies. After the war, she did it again when she saw Ingrid Bergman’s dresses in Saratoga Trunk.

One of her favorite films was Gone With The Wind. She named me Ashley after the character Ashley Wilkes played by Leslie Howard in the film. Her favorite actors were Clark Gable, Kirk Douglas and Stephen Boyd.

During Manila Film festivals, she would bring us to watch one or two movies on the first day. There were usually long lines of people wanting to watch the festival movies but the long lines never bothered her. She simply approached the man or woman near the front of the line. She then offered to pay for his / her ticket for Loge (more expensive than Orchestra or Balcony) if s/he would buy tickets for us. That usually did the trick.

In late 1969, her niece convinced her to convert her uninhabited house in her hometown in Davao del Sur to a restaurant. Later, the restaurant was turned into a movie house. Both ventures failed to make a profit. Later, her brother convinced her to turn the movie house into a mosque.

Around 1969/1970, when she had quite a lot of money, she kept on talking about producing a movie about the Battle of Padang Karbala. She wanted to get Omar Sharif and Ricardo Montalban to star in the film. It was only much later that I learned that the Battle of Padang Karbala was what the Mranaos call the Battle of Bayang, the first battle between the Moros and the Americans. I suppose she wanted Omar Sharif to play the role of her Arab grandfather and Ricardo Montalban as the Sultan of Bayang.

She brought actors like Johnny Delgado, Apeng Daldal, Sophia Moran and actors/singers Linda Alcid and Darius Razon to Mindanao either for shows or political campaigns. In the early 70s, film directors like J. Eddie Infante frequented the house, persuading her to produce a film. If I were older then, I would have encouraged her to make films. Perhaps she would have found fulfillment there. She never had a proper “career”.

When my father was still alive, she was known for hosting great parties. I still remember the last party she threw for their wedding anniversary, months before my father suddenly passed away. The very long buffet table was full of the most delicious foods. She, like her mother, was a great cook. As a 5-year old then, my role was to go around and offer cigars to the gentlemen guests. When I finally started writing regularly for a newspaper, I wrote three feature articles on Mindanao mentioning her in 1999/2000. They were my tribute to her. I think she liked them.

The Marcos connection

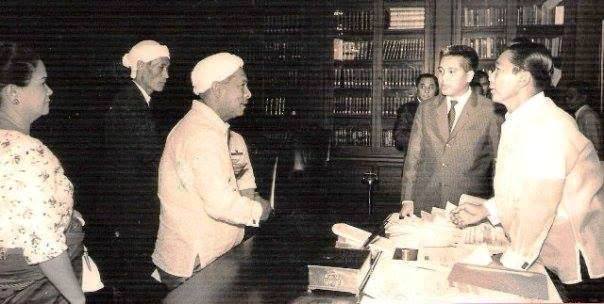

Nineteen sixty-nine was a huge year for my mother. She was the designated food concessionaire for the months-long voyage to Mecca for the Hajj aboard the MV Gambela. That meant that she was going to feed a ship load of people for a few months. Talk about captured market! But first, their group had to convince President Marcos to approve the Hajj enterprise.

Their group, which included her son-in-law Mike Tamano, who was then the Chair of the Commission on National Integration (CNI), a Cabinet post, went for an audience with the President. After the pleasantries, Mr. Marcos began lecturing the Moro group. And nobody among the Muslims seemed to want to speak for the group. Everyone, except Marcos, seemed tongue-tied.

According to my mother, she felt angry and frustrated. The prospect of selling food to a shipload of hungry people for 2 to 3 months was slowly slipping by. She gathered all her strength and walked to the table of Mr. Marcos. She banged the table and said, “Mr. President, you told me once that if I needed anything, I’ll just have to ask you!” Everybody in the room was shocked and dumbfounded. The President asked her, “And who are you?”. She replied, “I’m Sitti Rahma Peralta Yahya Abbas.” The President took a long look at her and said, “You are like a ghost from the past…” And as they say, the rest is history.

My mother went to the Hajj and got the Hajj name of Sitti Roweyna (pronounced Ro-Wai-na).

My mother’s grandfather was Don Mariano Salmon Peralta of Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte. who quite unexpectedly, got a Moro princess for a wife — Bai Mukuy (aka Colasa Bambang) of the Rajahnate of Buayan – on his way to Malita together with the American Occupying forces led by Lt. Edward Bolton. Bolton was tasked to survey the Cotabato-Davao area and ended up as the first military Governor of Davao.

Mariano and Bai Mukuy gradually built stone by stone, coconut by coconut – of what eventually became a three thousand hectare coconut plantation called La Ilocana Plantacion. This became the core of what became the modern-day Malita where Mariano presided as the town Presidente from 1906-1922. Mariano brought in people from his native Ilocos while Moros from Cotabato, Lanao and Sulu came to Malita because of the Moro matriarch.

Don Mariano Peralta was a cousin of Don Mariano Marcos of Batac, Ilocos Norte. After the Nalundasan case, Don Peralta invited Don Marcos to stay in Davao. Don Peralta got him a temporary job as Deputado Gobernador of Davao. Not many people know that Don Mariano Marcos actually lived in Davao. But if you get Ferdinand Marcos’s autobiography, (Tadhana?), there’s a picture of his father with the caption: Gentleman farmer in Davao. (At least in the edition that I saw.) The Marcoses used to spend their summer in Malita as guests of the Peraltas. According to my mother, she spent quite a lot of time talking to Ferdinand as she always found him alone and far from young people his age.

In 1977, when I went for a vacation in Malita, I was surprised to realize that my Peralta cousins looked like the Marcoses! Once, I was talking with some of the older people among the common folks. I asked them why they liked Marcos. And they said, “Marcos is from here — Malita!”

My mother got her ship, and made a killing. To everybody’s surprise, Marcos chose Mike Tamano to be part of the Nacionalista Party’s Senate line-up. My mother took the opportunity to introduce herself to Marcos’s mother, Dona Josefa Edralin Marcos. My mother spoke fluent Ilocano so she felt at home with Nana Sepa and her entourage. Together, they created Operation Pepay. Campaign funds came pouring in. I’ve never seen such amount of campaign funds in my life. Nana Sepa and my mother became life-long friends.

When Nana Sepa died in 1988, my mother, my eldest brother Jun Abbas and I went to her wake. A lot of press people were there, and they were quite shocked to see my brother, a staunch Marcos oppositionist, attending the wake of Marcos’s mother. They did not know, of course, that Nana Sepa used to call my brother, “My Golden Boy.”

Widow with eleven children

My father died in 1964 leaving my mother, 46 years old, with 11 surviving children. I was only 5 and half years old then. Her two eldest daughters were married but her two eldest sons – the famous Abbas brothers (Macapanton, Jr. and Firdausi) who later became senatorial candidates – were still in college.

To this day, I don’t understand why, with 9 unmarried children, she did not return to her hometown where she had a house and what was left of her coconut plantations. She could have been with her mother who had land properties in the town proper; and, her brother who was the mayor; and her whole maternal clan who lived there as the region’s elites.

Instead, she lived life the way she apparently wanted to – independently. She never remarried although she had marriage offers from rich and powerful men.

My mother taught me a lot of things, like the love of movies and poetry. She taught me the first poem I liked – The Invictus by William Ernest Henley. As a child, she kept on repeating to me that although there would be times when I would not be an “aristocrat of the purse”, I would always be an aristocrat “of the blood and of the intellect.” Unfortunately, in the Age of Mediocrity, it is the purse that counts.

=================================================

SEE RELATED POSTS:

My mother’s father and grandfather: Sheikh Yahya ibn Hadi and His Descendants

My father: Macapanton Abbas, Sr. as a Young Man

My eldest brother: Remembering Big Brother Jun Abbas

3 thoughts on “Hadja Sitti Rahma Yahya- Abbas”