With the explosion of Information Technology, the amount of misinformation and disinformation multiplied since it can now be shared and distributed worldwide with just a click on the keyboard. And it remains in cyberspace, perhaps forever. Seemingly innocuous information could easily pass for facts.

I just saw on the Internet such misinformation about my father. Actually, I’ve read it more than 20 years ago, but at that time, I just laughed at its wrong information. I thought then that not many people would buy the book, anyway. But now that I read it again in the Internet, I realized that people might regard this info as actual facts. And it is now easily accessible. This blog post is written to correct this:

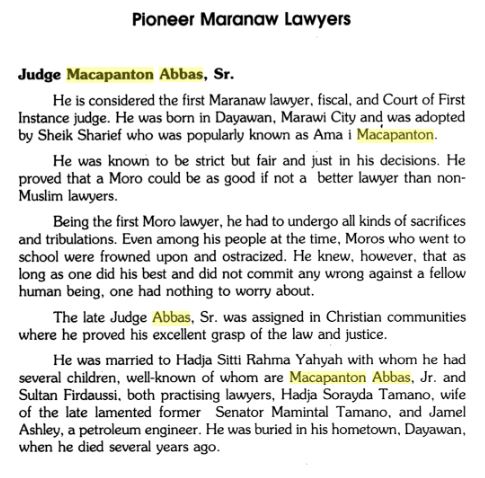

This is taken from the book Maranaws: Dwellers of the Lake by Dr. Abdullah Madale, husband of our cousin.

First off, my father was not just the first Maranaw lawyer, fiscal and CFI judge; he was the first Moro or Muslim Filipino lawyer, fiscal and CFI judge. I suppose he used Maranaw instead of Moro because the book is about Maranaws.

Second, who was Sheikh Sharief who was supposedly “popularly known as Ama i Macapanton (father of Macapanton)” ? The Ama i Macapanton that everybody knows was Cotawato, Sultan of Dayawan and the brother of Bai a labi Dalumabi, the biological mother of Macapanton.

Sheikh and Sharif are both titles used by Moros and other Malays for those whose fathers are Arabs or have continuous Arab male lineage.

My mother, whose father Sheikh Ismail ibn Yahya ibn Hadi was the son of a pure Arab, never mentioned that my father’s uncle and adoptive father was an Arab. The Arab community in Mindanao was quite closely knit.

It seems so strange that the author did not mention my father’s biological parents and his true relationship with Cotawato. In fact, he did not even mention the name Cotawato. The author’s wife is the daughter of Cana, son of Cotawato. Cana was the first cousin of my father as well as his adoptive brother. Cotawato was popularly known as Ama i Macapanton (father of Macapanton) and not Ama i Cana).

Or maybe Mr. Madale has the impression that Cotawato was not the same person as this mysterious Sheikh Sharief.

As I wrote in My Father As A Young Man,

Macapanton (was) born to Hadji Darapa Abbas, the Datu of Marawi, who was the son of Hadji Okur, the Rajah Muda of Marawi, who was in turn the son of Rampatan, the Datu of Marawi. The rank/title of Datu of Marawi is firmly in the line of Macapanton’s patrilineal heritage.

The Datu of Marawi was the Defender of Marawi. Up to that time, the Mranaos never paid any taxes to the Spanish or the American colonial governments. The Mranaos, as most Moros, paid tributes or zakat to their feudal leaders. The people of Marawi paid tribute to the Datu of Marawi.

Macapanton’s mother was Bai a labi Dalumabi, sister of Cotawato, who was the Sultan of Dayawan and Wato. Her other brother was Bacarat, who also became Sultan of Marantao.

Upon Macapanton’s birth at the Dayawan torogan (royal house), his uncle Cotawato and his wife (Paramanis?) adopted him. According to my mother, Cotawato’s wife was the sister of Hadji Abbas. Adopting nephews and nieces was quite usual among Mranao families. Adopted children also acquire the rights and privileges to the ranks and titles of their adoptive parents. Thus, Macapanton and his descendants held the rights and privileges to two sets of royal bloodlines.

And so, third, my father was not just a poor orphan adopted by a complete stranger named Sheikh Sharief, as could be inferred from Madale’s description. Quite the contrary.

Fourth, my father “being the first Moro lawyer” was supposed to have undergone “all kinds of sacrifices and tribulations”. What exactly were those? He breezed past through his studies — from elementary to law school. He got a government scholarship in high school and when he was studying at the Philippine Law School, aside from allowances from his parents, he also got extra money from his uncle the Sultan of Lanao who was in Manila as Congressman of the Third District of the Province of Mindanao and Sulu. He acted as his uncle’s part-time secretary and interpreter. He appeared to be active in student leadership, being the head of a fraternity in their school, a founding member of Young Philippines Party and Pan Malayan People’s Union.

My father indeed suffered “sacrifices and tribulations” during the Japanese Occupation. But that was not because he was the “first Moro lawyer”. At that time, there were already other Moro lawyers like Datu Duma Sinsuat and Datu Domocao Alonto. He suffered because he refused to join the Japanese government, until he decided to surrender in 1943 because his youngest daughter died due to their being constantly on the run. She was just an infant.

He wanted to join the guerrilla movement but his wife refused. So, together with his wife, his wife’s mother, their 4 small daughters, and their servants, they had to go on hiding, if they were not running away from the Japanese.

Fifth, Madale wrote: “Moros who went to school were frowned upon and ostracized.” Again, that needs CONTEXT. In order to better control the subject people, the Americans insisted on compulsory elementary education for everyone in the Islands. The Moros, esp. the Mranaos, refused because they believed that the Americans were out to Christianize the Moros, just as what the Spaniards tried to do before.

Some more progressive Mranaos sent their children to school, like my father and my mother. But they were very few and far between. So, the Americans became very insistent. They believed they could acculturate the people better by teaching them their (the American) ways, esp. their language (English).

To appease the Americans, esp. since the Americans changed from military control to a more peaceful civilian control, the Mranaos acquiesced – sort of. Instead of sending their children to American schools, they sent the children of their slaves. The Americans had no idea what was going on.

Thus, many of those slave children who went to school could have been “ostracized and frowned upon.”

In the case of my mother, for example. her father, a very progressive Arab-Mranao, had her placed in a dormitory school for girls in his hometown of Bayang in Lanao. When the Bayang datus heard of it, they surrounded the school and demanded that the American headmistress surrender my mother to them or they would burn the school down.

The Bayang datus were horrified that my mother, Sitti Rahma, would live, eat, and study among the children of slaves. My grandfather had no choice but to get my mother out of Lanao and enrolled her in a dormitory school in Cebu.

My father, who belonged to the datu class, was neither ostracized nor frowned upon, In fact, after elementary school, he insisted on studying high school in Manila.

Sixth, that my father “was assigned in Christian communities” is only partially true. After passing the Bar, he practiced Law in Marawi until the advent of World War II. In 1943, he was appointed Justice of the Peace in Lanao.

It was only in 1947 and 1948 that he was appointed to a Christian community as First Assistant City Attorney of Davao City.

But in 1949, Macapanton was sent to a Muslim community as Provincial Fiscal of Sulu. In 1954, he was appointed District Judge of Sulu and Basilan City by President Magsaysay. Two years later, he was promoted by Magsaysay to CFI Judge of Sulu.

In 1958, Abbas was transferred from Sulu to Davao as CFI Judge of Davao and Davao City. Before becoming CFI Judge of Davao, he spent most of his time in Muslim communities — in Lanao from 1936 to 1947 and Sulu (including Basilan) from 1949 to 1958.

And lastly, my name is Jamal Ashley, not Jamel Ashley.

The errors in Mr. Madale’s short write-up on my father are quite incredible. I wonder about the content of the rest of that book. Writers should not just write anything without checking their facts. They cannot just make things up. Publishers should have Fact-Checkers.

with the legal luminaries of Zamboanga, Basilan, Sulu, and Tawi-Tawi

===========================

See Torogan, the Mranao royal house (esp. the POSTSCRIPT section)

1 thought on “Misinformation, Disinformation, or Lack of Research ?”